Chinese Young Adults’ Sense of Self in Social Media: Through the Lens of Beauty Apps

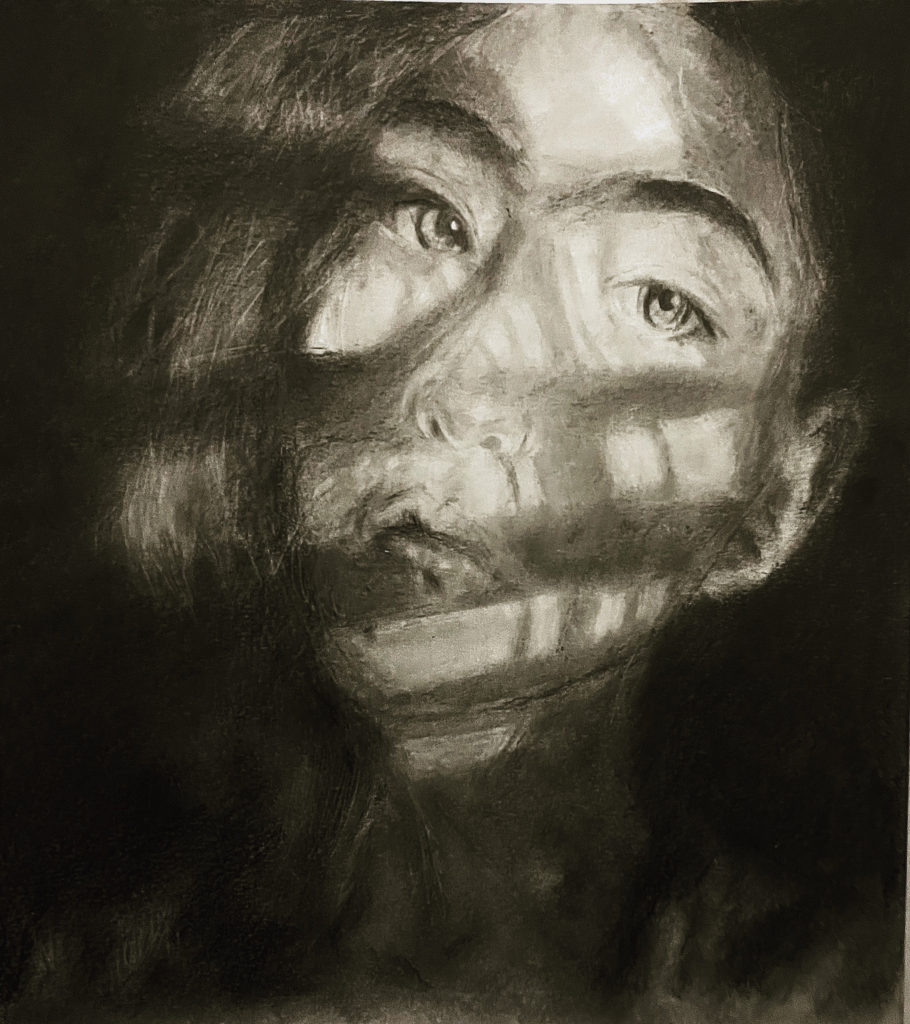

Image credit: Self-Portrait during Quarantine, by Shumei Tang 唐舒眉

JIA ZOU

Read the Faculty Introduction.

Since photo-editing apps have emerged in China, Chinese young people are spending lots of time and effort editing their selfies using all kinds of beauty apps, before posting them online. In “China’s Selfie Obsession,” Jiayang Fan points out one disturbing phenomenon caused by these beauty apps: they are making young people’s selfies look more and more homogeneous: all with big eyes, double eyelids, pointed chins and pale white skin, flawless yet losing authenticity (Fan). This phenomenon is disturbing, because scholars agree that selfies are “a valuable means of self-presentation and self-expression” in social media cultures nowadays (Lobinger and Brantner 1849). Homogeneous selfies mean that young people are not expressing their real selves through this valuable means of self-presentation. As Fan argues, “the freedom to perfect your selfie does not necessarily yield a liberated sense of self” (Fan). In other words, Chinese young people’s self-representation through inauthentic selfies distorts their sense of selves. They create the illusion that they have expressed their individualism by achieving their ideal self-image, which is in fact not their true self, as they are conforming to the social aesthetic standard. I agree with Fan’s opinion that the inauthentic selfies posted by Chinese young adults are associated with lower self-esteem. However, a selfie with authentic self-representation does not necessarily mean higher self-esteem, because of the subconscious existence of self-objectification. By considering the recent trend, several years after Fan’s article was published, where more and more Chinese young people are appreciating less-edited selfies on social media, I argue that these selfies may not be authentic self-representations. Instead, unedited selfies that are posted without seeking outside confirmation are less affected by self-objectification and truly have a stronger sense of self.

The concept of “sense of self” is not yet strictly or scientifically defined by scholars. However, as a branch of self-concept, “sense of self” involves ideas like self-esteem (Skoglund). Self-esteem refers to a person’s overall sense of personal value or worth. It can be considered as a measure of how much a person “values, approves of, appreciates, prizes, or likes him or herself” (Adler & Stewart). Another concept, which can also be regarded as one branch of “sense of self,” is self-objectification. Self-objectification is defined as “the adoption of a third-person perspective on the self as opposed to a first-person perspective” such that people who post selfies “come to place greater value on how they look to others rather than on how they feel or what they can do” (Calogero 575). It refers to an individual’s internalization of an observer’s perspective as a primary view of their own self (Zheng 325). In other words, self-objectification happens when people look at and evaluate themselves as objects based on appearance. “Sense of self” is a complicated concept that of course includes more than these two components, but this essay will focus mainly on these two aspects.

To figure out the relationship between a person’s sense of self and the authenticity in their selfies posted on social media, the concept of “expressive authenticity” needs to be employed, following the work of Marcus Banks. A photograph achieves expressive authenticity when the representation of the person is consistent with their own nature (Banks 168). In other words, we regard a selfie as having expressive authenticity when it is an honest expression of the user’s true appearance, personality, and beliefs. “Authenticity” in my essay mainly refers to expressive authenticity based on Banks’ theory, which means that the photograph is not only less-edited technically, but is also closely related to the true self of the depicted person. The following image is an illustrative example of a photograph that demonstrates expressive authenticity:

The selfie above, taken from Zhihu, which is the largest question-and-answer platform in China, is a highly rated answer under the question “What do you think of people who post selfies without any Meitu processes?”. This user posted a caption along with her selfies that said, “Most people regard beauty as features like white, flawless, big eyes, slim, etc. But beauty should be diverse and tolerant and I like myself with flaws, with my freckles, pimples, and black circles.” Her selfie has the property of expressive authenticity as she looks natural rather than staged, authentic to what she looks like in real life. The girl stresses that she didn’t edit the selfie at all while admitting and embracing the existence of the “imperfections” on her face.

On the other hand, inauthentic selfies basically include the features appearing in Fan’s article as wang hong lian (“internet celebrity face”), as shown in Fig. 2: double eyelids, big round eyes, white skin, and small mouths, as a result of having the selfies heavily perfected using Meitu apps (Fan). Such selfies do not have expressive authenticity, because the selfie cannot really represent the person depicted, as not only his or her appearance, but also the state of life shown, is faked into an ideal yet dishonest and unnatural image.

A lower level of self-esteem will result from young Chinese posting more inauthentic selfies, as they use photo-editing apps as tools to achieve their dreamy self-images, losing confidence in their true selves. Rachel Grieve et al.’s study “Inauthentic Self-Presentation on Facebook as a Function of Vulnerable Narcissism and Lower Self-Esteem” reveals the congruence between self-representation on Facebook and the participants’ true selves. According to the researchers, “for individuals with average and low levels of self-esteem, there is more incongruence between the true self and the Facebook self (as a function of increased vulnerable narcissism)” (144). Though Grieve et al.’s research was on Facebook, we can still see similar phenomena happening in Chinese social media: those who spend more time and energy editing a selfie to a “perfect” one before posting it online, such as the internet celebrities described in Fan’s article, tend to care more about the likes and followers they receive. When they edit their selfies, they tend to focus more on the “unsatisfying” parts of their appearance, denying their own unique features. Their actions imply the negative self-perception that they do not think people would accept who they really are, signifying their low self-esteem. Young people can be trapped in this vicious cycle, just like the internet celebrities in Fan’s article, who stare at their phones all the time to see whether their new posts have gone viral (Fan). As Grieve et al. claim in their research, “greater discrepancies between the [true and Facebook] selves may be indicative of an individual attempting to mask feelings of inadequacy” (148). Because these young people have comparatively lower self-esteem, they care much about what other people think about their selfies and want to exhibit a perfect image of themselves; however, as they over edit their selfies, they deny their own images, conforming to the social aesthetic standards, instead of accepting or even admiring their uniqueness, leading to an even lower self-esteem.

Much different from the homogeneous and inauthentic beauty described in Fan’s article, Chinese young people have started appreciating natural and authentic selfies more and more in recent years. One example of this trend is the heated “Selfies without Editing Contest” on Weibo starting from 25 April 2020, with 100 million “reads” and 20 thousand “discussions” so far (Fig. 3). In addition, a new BeautyCam app named Qingyan Xiangji, released in 2018, which focuses on natural filters and especially avoids wanghong editing styles, has gone viral, and now occupies a large share of the beauty camera app market in China (@CharisApril). In the study “In the Eye of the Beholder: Subjective Views on the Authenticity of Selfies,” researchers Katharina Lobinger and Cornelia Brantner examined how people’s evaluation of the selfies posted on social media is affected by the photographs’ expressive authenticity. They found that some participants regard selfies as “inauthentic” because of the apparent staging or visibility of the photo editing process. Their research also suggests that teenagers admire photos showing people in “natural, everyday situations” instead of “artistic and visually scripted or composed pictures” (1856). It can be seen that expressive authenticity has become an admirable quality in this new trend.

However, a selfie with expressive authenticity is not equal to authentic self-representation in the selfie, even if the person has high self-esteem, because of the influence of self-objectification. According to Dong Zheng et al.’s study on Chinese adolescents on social networking services (SNSs), their selfie-posting behaviors on Qzone were positively associated with self-objectification. This relationship is specifically moderated by imaginary audience ideation, which refers to the assumption in one’s mind that others are “looking at and thinking about oneself all the time” (326). Therefore, when young people post selfies on social media, they are preoccupied by the idea that a group of imaginary audience would be gazing at their images and evaluating them based on their appearance. For instance, winners from the “Selfies without Editing Contest” on Weibo, who received more likes and comments than others, all fit into Chinese beauty norms, with fair skin, big eyes, and slim bodies. They also promoted their selfies to seek complimentary comments, and enjoyed increased likes and followers on their platforms as a result of being rated high in the contest. No matter how “authentic” the selfies posted by people with high self-esteem are, they are still under the process of self-objectification, subconsciously seeking for positive feedback from the “subjects,” namely, other people who are viewing and judging them.

The selfie on Zhihu in Fig. 1, belonging to the girl whose image demonstrates expressive authenticity, further emphasizes this point. Her entire post actually emphasizes the technical tips to take a beautiful selfie that will gain likes and followers on social media, using just a smartphone camera and without photo-editing apps. When people emphasize on social media that their selfies are “not edited,” they are actually seeking a sense of satisfaction from others’ compliments. In other words, they post selfies with expressive authenticity that are not staged or edited; but they post them only as evidence of “I look beautiful even without any Meitu process”. It is true that these young people may have higher self-esteem, as they have the confidence and courage to post unedited authentic selfies that highly represent their true self. However, they are still stressing to their imaginary audience that they did not edit their selfies, reflecting how much they care about getting compliments from others, to confirm their beliefs that they are beautiful. Self-objectification is thus almost always playing a subtle role when Chinese young people post authentic-like selfies, even for those who have high levels of self-esteem.

Compared with those who post authentic selfies with captions that emphasize how their selfies are “non-edited” or “filters-free,” young people who post authentic selfies without highlighting this fact are less affected by self-objectification. According to the study “Clarifying the Relationships Between the Self, Selfie, and Self-Objectification: The Effects of Engaging in Photo Modification and Receiving Positive Feedback on Women’s Photographic Self-Presentations Online” led by Megan Vendemia, engaging in the selfie modification process does not affect the state of self-objectification significantly; however, receiving comments on one’s appearance would increase the level of self-objectification (37). Though the study mainly focused on women, some findings can still be applied to young social media lovers as a whole: it is not the photo-editing process, but receiving favorable feedback that heightens self-objectification for people who share selfies on social media, enticing them to focus on their appearance as “a valued commodity” (40). Young adults who post unedited selfies without any sign of looking for outside compliments, in contrast, are more likely to be accepting of what they look like, including those parts of their bodies that are regarded as “imperfect” when examined by social media norms. As they do not depend on receiving favorable comments on their appearance to gain their sense of self-worth, such behavior can be considered as lower self-objectification. Interestingly, there is no measure for determining the reason why they are not stressing the fact that their selfies are unedited — while they might not care about outside confirmation, they may also believe that their natural appearance is good enough for receiving favorable feedback, and therefore are still seeking external confirmation consciously. Therefore, even when a photo demonstrates expressive authenticity, it does not necessarily demonstrate authentic self-representation.

Young social media users may always be looking for favorable feedback like complimentary comments, likes, and the number of followers, when they present themselves through selfies on social media platforms. In other words, self-objectification always seems to be playing a part in self-presentation on social media, whether through heavily edited or unedited selfies, and unedited selfies posted without drawing people’s attention to their expressive authenticity. On a superficial level, low self-esteem is associated with more inauthentic self-representations. In this case, expressive authenticity is not achieved, since the person’s true self is either distorted or hidden by the photo-editing process. However, higher self-esteem does not necessarily lead to authentic self-representation, because of the subconscious existence of self-objectification, which entices young adults to stress the non-edited aspect of their selfies, in order to gain likes on social media. In turn, these likes allow young adults to gain a sense of self-value. Therefore, despite the decreasing popularity of wanghong-style selfies in China, in favor of less-edited selfies, Chinese young social media users need to recognize that their self-worth is embedded neither in heavily edited selfies nor the texts posted along with the selfies. To gain a better sense of self-worth, they need to hold the belief that their natural appearance can be appreciated no matter what, as long as they believe that they are representing their authentic selves.

Works Cited

Banks, Marcus. “True to Life: Authenticity and the Photographic Image”. Debating Authenticity. Concepts of Modernity in Anthropological Perspective, Edited by T. Fillitz & A. J. Saries, Berghahn Books, 2012, pp.160–171.

Calogero, Rachel M. “Objectification Theory, Self-Objectification, and Body Image.” Encyclopedia of Body Image and Human Appearance, Edited by Thomas F Cash, vol. 2, San Diego: Academic Press, 2012, pp. 574–580.

Fan, Jiayang. “China’s Selfie Obsession.” The New Yorker, 11 Dec. 2017, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/12/18/chinas-selfie-obsession. Last accessed 9 April 2021.

Grieve, Rachel, et al. “Inauthentic Self-Presentation on Facebook as a Function of Vulnerable Narcissism and Lower Self-Esteem.” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 102, 2020, pp. 144–150.

Lobinger, Katharina and Brantner, Cornelia. “In the Eye of the Beholder: Subjective Views on the Authenticity of Selfies.” International Journal of Communication, vol. 9, 2015, pp. 1848–1860.

Skoglund, Elizabeth R. “Self-Esteem, Self-Love.” Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, edited by Walter A. Elwell, Baker Publishing Group, 3rd edition, 2017.

Vendemia, Megan A. “Clarifying the Relationships Between the Self, Selfie, and Self-Objectification: The Effects of Engaging in Photo Modification and Receiving Positive Feedback on Women’s Photographic Self-Presentations Online.” The Ohio State University OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center, 2019.

Zheng, Dong, et al. “Selfie Posting on Social Networking Sites and Female Adolescents’ Self-Objectification: The Moderating Role of Imaginary Audience Ideation.” Sex Roles, vol. 80, no. 5/6, 2019, pp. 325–331.

@CharisApril. “轻颜相机产品分析报告 –‘颜值时代‘下的‘她经济.’ Product Analysis Report of Qingyan Xiangji — ‘Her’ Economy in the ‘Beauty Era’.” 简书, 16 March, 2019, www.jianshu.com/p/758fa8a72c9a. Last accessed 9 April 2021.

@小枫儿童成长学. “Example of Wanghonglian”. Kandiankuaibao, 9 December 2019, https://kuaibao.qq.com/s/20191209A0OF0700?refer=spider

Recent Comments