Identities and Linguistic Features in Computer- Mediated Communication

Image Credit: Jiannan Shi

Zhirui Yao 尧之睿

I. Introduction

Over the last ten years, the internet has developed faster than anyone could have imagined. Along with this development has come the rise of computer-mediated communication (CMC), also known as online communication. Unlike traditional face-to-face communication, people don’t have to respond instantly during online communication, which gives them time to think about how they want to present themselves. The identities shown through CMC are, therefore, “more malleable” and “more subject to self-censorship” (Ellison et al. 418). People seem to have more power over their presentation of their identities through the channel of online communication.

In this essay, I will discuss incentives for presenting certain identities and examine how the intentions behind those identities are being carried out through people’s various language use in CMC. Here, identity is defined as the image people show to the outside world about themselves that meets both individual desires and external expectations towards the individual. Desires, here, can refer to “[the] desire for recognition; quest for visibility; the sense of being acknowledged; a deep desire for association…,” while the expectations denote the anticipation one senses that others have towards them (West 20). I argue that people implement communicative skills that are specific to CMC to build their social identity for the purpose of being accepted by targeted interlocutors or the general public.

2. Methods

I) Data Sources and Selection Rationale

The data selected comes from my WeChat conversations with my friends, and my friends’ chat histories. These sources contribute to my discussion by illustrating the different incentives for identity performance. These sources are selected based on the possibility to investigate the actual context of the conversations. This critical selection criterion aims to reduce misunderstandings between the researcher and the data resources, and it adds credibility to the analysis.

Furthermore, in order to understand the identities presented in CMC on a larger scale, I also include one screenshot from Weibo, a mainstream social media outlet in China. The Weibo content selected has been reposted hundreds of times or comes from bloggers with over ten thousand fans online. The widely read materials with special expressive features illustrate typical identities presented in the Weibo environment and lead to the disclosure of repeated cultural patterns behind web language use.

II) Analytic Methods

In order to protect the privacy of the interlocutors in WeChat conversations, their names and relevant identifying information were modified during data preparation. Weibo users’ usernames were also masked. When examining WeChat conversations, I adopted the “speaker-driven method,” which relies on the specific context of each instance of language use (Clark 152). I interviewed the main interlocutors to find out why they applied certain linguistic features. The special ways of communication in WeChat conversations were categorized to find out the identities being performed. When analyzing the larger groups’ conversations in Weibo, I also summarized one of the most frequent identities observed, connecting it to the definition of identity. Lastly, a connection between small group dialogues and large group conversations was made to look into how micro and macro level identities are carried out.

3. Results and Discussion

I) Data and Analysis

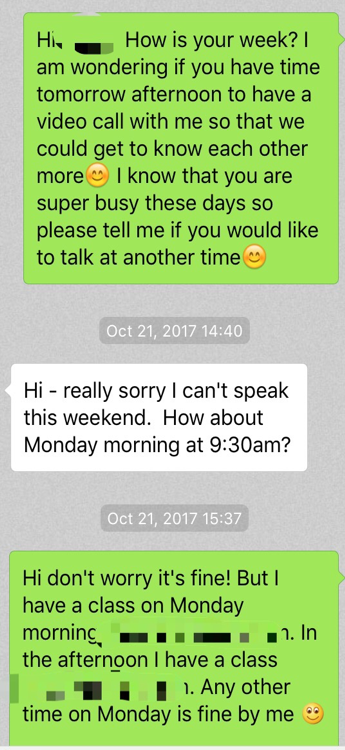

Figure 1 is A’s conversation with her alumni mentor (B). B is more experienced in the industry than A is, and more importantly, he occupies a very high position in this industry, which gives him the credibility to give other people suggestions. In this screenshot of the conversation, A is asking B whether he has time to hold a video call with her on Monday to give her career advice. She begins this conversation by politely greeting him so that her request will not seem too abrupt. What is more worth noticing is her use of emojis. In just a few sentences, she uses the smile emoji three times to show that she is genuinely looking forward to having a video call with B. This repetitive use of emojis represents her effort to be a friendly and involved junior who is eager to learn from an expert. Also, A puts all the information in a single block instead of separating it into sentences. This short-paragraph format exhibits her formality when talking to B since she in trying to give B the impression that she has thought thoroughly before sending the messages. Compared to B, A also gives a much more detailed and therefore longer explanation of her plans, while B simply uses a hyphen (-) to connect two short sentences without giving specific reasons for his unavailability (see the white bubble from B in Figure 1, above). Furthermore, when B makes a proposition, he directly offers his preference by asking a question starting with “how.” However, when A makes the request for them to meet, instead of directly asking the question “do you want to meet tomorrow afternoon?” she starts out by using “I’m wondering” to serve as a buffer for her following inquiry for politeness. The use of the present continuous tense in “I’m wondering” implies that there is something on A’s mind that makes her undecided about whether her request is plausible, and the reason could well be explained by her following sentence—the assumption that a senior professional, her alumni mentor, must be incredibly busy with his work, and is probably unable to spare some time for her. In contrast with A, B is not too worried about what response his proposal will receive. He gives a specific time on a specific day depending on his availability and waits for accommodation on A’s part. Overall, A is putting herself in a position that is lower than B’s so that B will be more willing to help her. She performs her identity as a modest learner, a polite and considerate negotiator, and a rookie who desires to be recognized and accepted by her alumni mentor, so she uses emojis, greetings, detailed explanation and complete paragraphs of speech to highlight her intentions. It is not the linguistic features she presents that makes her a student seeking advice. Instead, it is the desire to get help from B that determines her language use in CMC.

A’s slight change in attitude after she receives B’s response is worth noting. The power dynamic between A and B is not completely hegemonic, but fluid. After getting the slightly disappointing message from B, A does not use the iPhone smiley emoji but uses a unique emoji that only WeChat provides: a plain smiley face without the smiling eyes and blushing cheeks. This downgraded level of excitement, which in the conventional use of emojis in Chinese WeChat culture is associated with passive-aggression, shows how A is adjusting her attitude to be less ardent in response to B’s calmness. Unlike face-to-face communication, CMC gives interlocutors a chance to show their emotions at different levels without being noticed by the other side. People can play with their use of emojis and stickers especially when the responding interlocutor is unfamiliar with the web-cultural context of how such expressions are used. However, it’s also clear that A does not want B to take her message to be negative. She chooses an emoji with passive connotations in her own culture but positive meaning in B’s culture. A is still trying to perform her identity as the moderate junior like before, despite the covert resistance carried out by the WeChat smiley emoji. From this dialogue, we can observe interesting changes in emotions and the power relation between the two interlocutors that are either purposefully revealed by CMC featured language use, or clandestinely hidden under specific cultural meanings. Speech performance is part of identity performance, and people’s desire to be recognized and respected prompts their various linguistic choices.

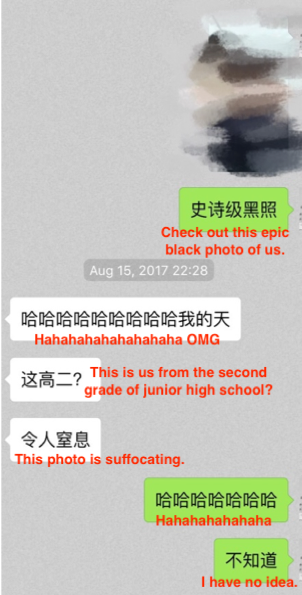

The same relationship between language use and identity can be observed in my conversation with one of my very close friends as well (see Figure 2). In this case, our power relation is equal, and we are not asking each other for any specific benefits. Our linguistic features in CMC exhibit more of our attitudes towards each other’s expectations. In Figure 2, I send her a terrible selfie of us taken two years ago and describe it as an “epic black photo” (“black” stands for “bad” in Chinese internet language). I exaggerate the degree of ugliness of this photo by using the adjective “epic” and “black” to show my shock towards this photo in a more humorous way. In response to my efforts to be humorous, she replies with a long sequence of “ha.” While she might be amused by my description of the photo, in real life she would probably not laugh this hard. The use of extra “ha”s is her effort to be a good friend of mine and respond to my jokes. Later on, she asked me which grade the photo was taken in and described the photo as “suffocating (because of its ugliness).” This expression can also be considered a response to my previous use of the word “epic,” with the same exaggeration. I also reply with a long sequence of “haha” to show that I appreciate her getting what I want to complain about in this photo. Here, both of us have actively responded to each other’s words to make the conversation more easygoing and fun, and therefore the identity we both present is “a good friend who gets the other person.” It is because of our genuine hope to be more connected with and therefore more recognized by each other that we speak in this way. Language is our medium to embody this desire and perform specific identities.

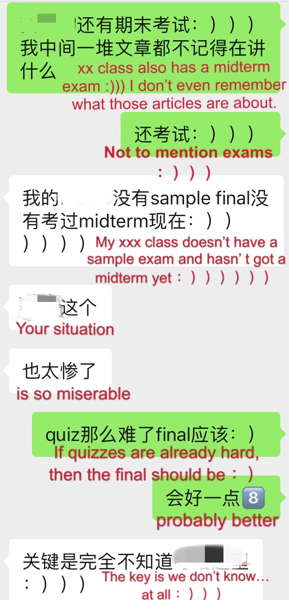

A similar example is the dialogue between my friends C and D (see Figure 3). In this scenario, the two interlocutors are discussing a final exam and complaining to each other about how unprepared they are. We can see that the green bubble starts out with a series of complaints followed by “: ) ) )”, a variation of another passive-aggressive smiley emoticon “: )” for the purpose of emphasizing the intensity of emotion. Later, this pattern of icons is followed by the other interlocutor, as represented by the white bubble. The white bubble even adds more closed parentheses to the original modified smiley emoticon to stress how he feels the same about the exam with the green bubble (see the first and last white bubbles in Figure 3, left). The two interlocutors, while they might have different speech habits in daily life, exhibit similar expressions as their conversation goes on. Although the green bubble doesn’t explicitly state his expectation towards the white bubble that he should empathize with him and follow his use of the smiley emoticon, the white bubble nevertheless responds by putting himself in the green bubble’s shoes and behaving according to the green bubble’s rules of language, and probably his way of thinking. It can often be observed that people who chat more frequently online have similar speech patterns, and perform similar web personalities regardless of their actual qualities. Just like the above dialogue, our language use is being constantly modified and adjusted when we are facing different audiences. To put it in the CMC context, social media platforms extend our ways of expression. We are not only using words, but also textual portrayals such as emojis and emoticons containing special characters to express ourselves, acting as the active interlocutor the other side may wish to see. Thus, responding to expectations is another critical motive for the language features people present.

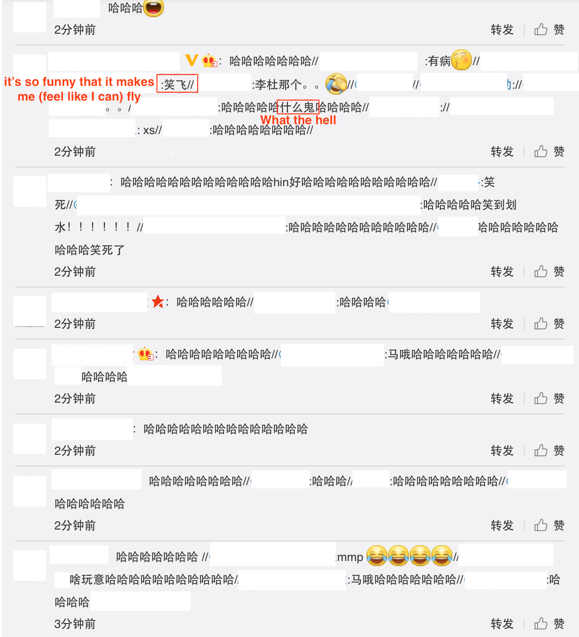

The three examples given above describe how in small group conversations, diverse linguistic tools can reflect people’s desires and responses to outside expectations. Not surprisingly, people’s expressions may also appear to be homogeneous when it comes to larger and more public discussions online. Figure 4 is a screenshot from a fun Weibo post recreating images of ancient Chinese figures. In the repost area, almost all of the repost comments are simply long sequences of “haha” (laughter) and their variations (see the second user’s repost area in Figure 4, Line 3). Although the users are reposting from different people, they concurrently follow the previous format of simply saying “haha.” Some even stress their amusement by using more ha’s than in previous comments to show their engagement in the public discussion (see the third user’s response to his previous repost comments in Figure 4, Line 6). Yet, hidden behind their similar language is their own emotions that may be distinctive from the general public’s. Almost nobody explicitly expresses any other thoughts about this post. Instead, people just laugh simultaneously.

Does this homogeneous linguistic feature mean that people have the same personalities? Not necessarily. But it at least means that people want to present themselves to the world in a shared identity in public discussions. Language endows people with identities. People’s use of abundant onomatopoeia “ha” illustrates their efforts to be a “haha dang 벗벗뎨” (party of haha), that is famous for laughing all the time in Weibo. The logic behind laughing all the time is fairly evident: people want to present a more easy-going character online. The logic behind being part of the “haha” party is also rather simple: since everyone is laughing so hard, one should also do so or otherwise it will make him look offbeat, even if he is only a little amused in real life. In this case, people no longer have control over what linguistic features they can apply, for that particular identity is tied to particular expressions. If they want to share that identity for a sense of security, they will also have to apply the same linguistic features and act according to the same set of online behavior norms. Regardless of the specific identity that people want to present in Weibo, language is their key to having that identity. In this case, language is the tool for people to identify their kind and distinguish others.

II) WeChat, Weibo, and Beyond

There are several observations we can make from the data above. To begin, it is quite clear that the presentation of identity to the world is a determinant of people’s use of language in CMC: “Whenever we isolate language from the people who speak and interpret it and the context in which they speak and interpret it, we are not getting closer to some kind of essential truth about language” (Joseph 24). If people don’t have desires or don’t care about external expectations, then there is no starting point for people to take on a certain form of language. In fact, it is doubtful that language would even exist.

Furthermore, as Walther has noted, since CMC is “asynchronous” and only “verbal and linguistic cues” that are “most at our discretion and control” are shown, people’s self-presentation online is “more selective, malleable, and subject to self-censorship” than face-to-face presentation (20). Therefore, in CMC, people are able to better utilize the linguistic properties of online communication, such as the application of extra onomatopoeia and emojis, the length and density of information, and the corresponding descriptive habits like exaggerating feelings, to consciously present certain identities. It is no longer enough to just consider language as a passive reflection of people’s identities. Language’s position as a stepping stone to gain a certain identity should be taken into consideration. In postmodernist theory, “people are who they are because of (amongst other things) the way they talk” (Cameron 49). Speech habits constitute identity performance. We may ponder how this phenomenon plays out in contexts other than CMC as well. For instance, scholars often tend to use similar terms and phrases in the academic field when they are talking about their research. To outsiders of the discipline, this makes them sound professional and worthy of trust. To insiders of the discipline, the use of shared verbal expressions reduces much of the trouble re-stating long and complicated concepts that are already considered common knowledge in the field. Different speech communities are thus formed on the basis of the same habits of expression people share, and people’s identities can be reshaped by language in a dynamic manner according to their needs—scholars don’t necessarily need to sound the same when they are at home and at work.

Last but not least, some properties of identity itself can be concluded. If the identity people present is subject to people’s tactical use of language, it means that the context and the way in which identity is performed can actively influence the meaning of each identity itself. The socially decided feature of identity can thus be seen. Identity can’t be interpreted separately without signifying people’s position in relation to others. The previous data show that the presentation of identity involves the desire to be recognized and accepted by others (West 20). This desire can also explain why, on larger CMC platforms, people’s expressions have the tendency to be similar. Public CMC platforms, such as Weibo or Twitter, are excellent stages for people to see others’ responses, and which responses are most welcomed. People adapt similar language features in order to have access to the same identity that secures them a sense of recognition and importance, just like what the “haha” party does on Weibo. This phenomenon is also common in other social interactions where people are obsessed with labeling each other with the same or different identities. As Golfman has pointed about the development of social interaction, “different acts [are] presented behind a small number of fronts” (17). While these small number of fronts can be the product of social organizations simplifying categories to save resources, they can also be people’s conscious choices to be included in a larger community to call for a feeling of protection, security, safety, and surety (West 21).

4. Conclusion

As the previous data and analysis show, language and identity can shape one another. Language exhibits the identity that people want the outside world to know about themselves. Especially in CMC, more communicative skills are applied when it comes to people showing their actual desires and responding to others’ expectations. More importantly, language can give people access to different speech communities, where they are able to gain the sense of security and recognition. Almost everyone is using language to simultaneously depict themselves and fit themselves into other social networks. Looking into the relationship between identity and language allows us a clearer understanding of people’s intentions behind their language use in CMC and in real life.

Due to project parameters, there is only limited time available to discuss the cause and effect of identities presented through CMC language use. Still, this paper can offer us important insights into many other social fields. For instance, when conducting identity studies, it is now vital to bear in mind that, on the one hand, we need to be skeptical when studying people’s comments posted online and analyzing their identities based on those comments, for they might be filtered or intentionally selected presentations of one’s real identity. On the other hand, an intense study of CMC language use may help researchers better dig into the reasons why certain identities are being performed online. The connection between a false exhibition of identity and CMC language use can also add comments to the field of education—young adults need to be guided to more sensibly select their CMC language use and critically reflect on popular comments online, so they are not misled and are not misleading others.

Some further research can be done to enrich the discussion. Behind the “performed” identities there remain two critical questions: why can these specific types of identities give people a sense of security? What are the dominant factors in deciding whether one identity is mainstream or not? A deeper analysis of the underlying social, economic, and cultural contingencies behind identities remains to be done by interested researchers.

Works Cited

Cameron, Deborah. 1997. Performing gender identity: Young men’s talk and the construction of heterosexual masculinity. In Sally Johnson and Ulrike H. Meinhof (eds.) Language and Masculinity. Oxford, U.K: Blackwell. 49.

Clark, Urszula. Language and Identity in Englishes. Routledge, 2013.

Ellison, Nicole, et al. “Managing Impressions Online: Self-Presentation Processes in the Online Dating Environment.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Blackwell Publishing Inc, 9 Aug. 2006, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00020.x/full. Accessed 29 October. 2017.

Goffman, Erving. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. University of Edinburgh Social Sciences Research Center, 1956. 17, www.monoskop.org/images/1/19/Goffman_Erving_The_Presentation_of_Self_in_Everyday_Life.pdf. Monoskop. Accessed 24 October. 2017.

Hulidabaoshi. “Shishang zui quan sushi san lian [The most complete version of the civilized three squads].” Sina Visitor System, Weibo, 26 Oct. 2017, weibo.com/2119801903/FsaH7v2nH?filter=hot&root_comment_id=0&type=comment#_rnd1509826039157.

Joseph, J. “Language and Identity.” Language and Identity: National, Ethnic, Religious, Palgrave Macmillan UK, https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1057/9780230503427.pdf. Accessed 24 October. 2017.

Labov, William. Sociolinguistic Patterns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972.

Walther, Joseph B. “Computer-Mediated Communication.” Communication Research, vol. 23, no. 1, 1996, pp. 3–43., blogs.commons.georgetown.edu/cctp-505-fall2009/files/computer-mediated-communication23.pdf. Accessed 1 Nov. 2017.

West, Cornel. “A Matter of Life and Death.” October, Columbia University Academic Commons, 1 Jan. 1992, academiccommons.columbia.edu/catalog/ac%3A157361. Accessed 26 Oct. 2017.

Recent Comments